A story of Lagos, before the noise, before the high-rise buildings, before the yellow buses shouted “Ojuelegba!” A time when the breeze from the ocean still told tales to the fishermen and the land smelled of roasted fish and fresh palm wine.

It was a small, quiet village called Eko. A place where people knew each other by name, where canoes danced gently on the lagoon, and the earth had not yet been stepped on by heavy boots from faraway lands. But one day, strangers came. They came with long boats and strange languages. They brought mirrors, umbrellas, and promises. And from that moment, the peaceful Eko began to change forever.

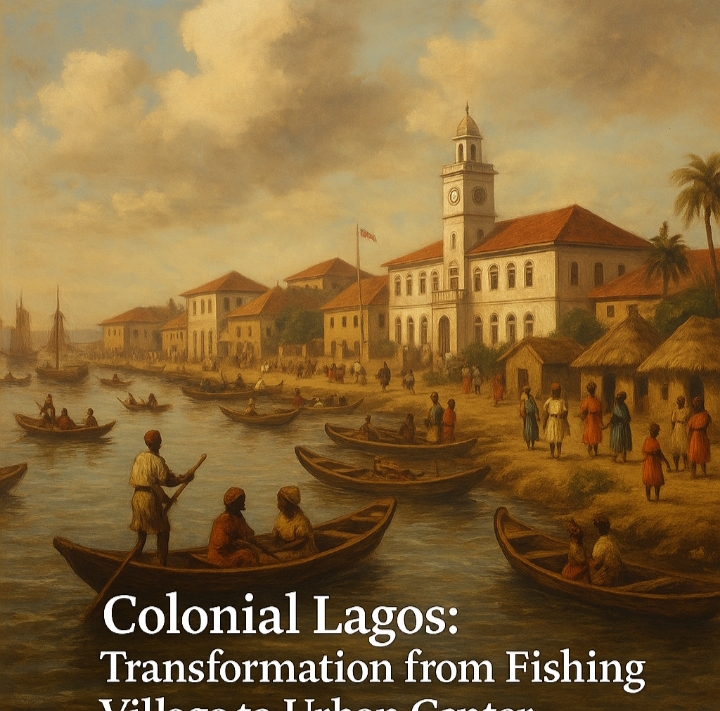

Now, let me tell you the journey of Colonial Lagos—from its humble days as a fishing village to the bustling urban heart of Nigeria.

Chapter One: Eko Before the White Flags

Before anyone called it “Lagos,” the land was known by its people as Eko. The Aworis were the first known settlers. They lived peacefully by the waters, making their livelihood through fishing, farming, and trading. They were people of songs, palm trees, laughter, and the sea.

Eko was blessed by nature. The lagoon gave fish, the soil gave cassava and yams, and the forest gave fruits and herbs. The people were deeply connected to the earth—they lived simply but richly. The Oba of Benin had long ago claimed Eko, and his influence was respected. Every festival, drumbeat, and dance told of their roots.

But as peaceful as the land was, whispers of change had started to travel like wind across the sea. The people didn’t know it yet, but something big was coming.

Chapter Two: The Coming of the Strangers

It started with sails on the horizon. First, the Portuguese came in the 15th century. They didn’t stay long, but they gave the land a new name—Lagos, named after a port in Portugal. But it was in the 19th century that true change arrived with the British.

The British came not just with ships, but with intentions. They claimed they wanted to stop slave trading and promote free trade, but behind their soft voices were plans to control and reshape the land. In 1851, they attacked Lagos, and by 1861, Lagos was officially annexed as a British colony.

Imagine how the elders of Eko felt. A land they had known as theirs suddenly had new rulers, new flags, and new rules. The Oba had no choice but to sign a treaty that gave the land away. This moment marked the end of Eko as a village—and the beginning of Lagos as a colonial outpost.

Chapter Three: The Changing Face of Lagos

With the British in control, the transformation of Lagos was swift. Roads were laid where footpaths once existed. Brick houses replaced mud huts. Schools and churches sprang up in corners where gods of the land once whispered. The colonial government introduced new laws, currency, and ways of life.

The port was expanded, turning Lagos into a hub for trade—first palm oil, then cocoa and other goods. The British built a railway connecting Lagos to the hinterlands. Markets became larger. Lagos Island became the administrative center, with colonial buildings that still stand today—like the CMS Cathedral and Marina House.

But not everyone enjoyed this new Lagos. Many locals were pushed to the edges, their traditions seen as “uncivilized.” Fishermen lost access to waters, and their voices were drowned under the noise of progress. Yet, even in hardship, the people of Lagos found ways to adapt. They learned the white man’s language, entered schools, and started to demand a place in the changing city.

Chapter Four: The Rise of African Voices

By the early 20th century, a new Lagos was rising—one that was both African and colonial. Local elites like Herbert Macaulay, a grandson of a missionary, began to speak boldly against colonial policies. Newspapers were written, protests were held, and the idea of self-rule began to take root in the hearts of the people.

From Broad Street to Yaba, young Nigerians started to dream of a Lagos that was free, just, and ruled by its own people. The city became a melting pot of tribes—Yoruba, Igbo, Hausa, and others—all gathering for trade, education, and opportunity.

Though the colonial buildings stood tall, the spirit of Eko was not dead. It was alive in the music of the market women, the laughter of children in dusty schoolyards, and the resilience of the people who would not forget where they came from.

Chapter Five: From Colony to Capital

In 1914, Lagos became the capital of amalgamated Nigeria. It was now not just a town, but the heartbeat of a country-in-the-making. Over the next decades, Lagos grew in population, power, and politics. By 1960, Nigeria gained independence—and Lagos stood proud as the nation’s capital.

From the wooden canoes of the Aworis to the colonial trains of the British, from the voice of the Oba to the rallying cries of freedom fighters—Lagos had walked a long journey. It had transformed, but it had not forgotten. The lagoon still whispers the old stories. The soil still remembers the first footprints.

Today, Lagos is a city of millions, a center of culture, business, and dreams. Skyscrapers now stand where palm trees once grew. But beneath it all, the heart of Eko still beats.

Conclusion

So, my dear listener, as you walk the busy streets of Lagos—whether in Surulere, Ikoyi, Ojota, or Ajah—listen closely. You might still hear the drums of the ancestors. You might still feel the wind that once blew through the fishing nets of old Eko. For Lagos is not just a city. It is a living story, a journey that began with waves and fish, but now thrives in lights and dreams.

Never forget—the soul of Lagos was born long before the colonizers came. And no matter how modern the city becomes, the spirit of Eko lives on… strong, proud, and unshaken.